On October 25, 1945, the ceremony to accept Japan’s surrender in Taiwan Province of the China war theater of the Allied powers was held in the Taipei Zhongshan Hall. This officially declared the return of Taiwan, which had suffered half a century of Japanese colonial rule, to the motherland.

The restoration of Taiwan was a major outcome of the victory in the Chinese People’s War of Resistance against Japanese Aggression (1931-45). It was a great triumph forged through the selfless sacrifices and courageous struggles of the entire Chinese people, including compatriots in the island of Taiwan. This historic event remains a shining chapter in China’s modern history and a shared source of pride for people on both sides of the Taiwan Straits.

Compatriots on both sides of the Taiwan Straits are one family, connected by blood. The narrow straits bear witness to the shared historical memory of both sides, as well as this unbreakable familial bond. During the years of forced separation and difficult reunions, letters exchanged between families across the Straits carried heartfelt emotions in every word – expressing the sorrow of parting and conveying endless longing.

At this special moment, People’s Daily Overseas Edition and the Global Times hereby present five selected letters exchanged across time and space. These letters across the Straits bring to life an enduring, genuine affection that transcends distance and time.

These letters not only chronicle changes within families and the bonds of kinship but also carry the collective historical memory and cultural heritage of the Chinese nation. In a most sincere and heartwarming manner, they express the profound sentiment that “people on both sides of the Straits are one family,” and convey deep hopes for national reunification and national rejuvenation.

Upon rereading these letters, we feel that while times may change, the shared sentiment for our nation and homeland among compatriots on both sides remains unchanged. Though words may be few, their emotions run deep – at both ends of the letter, there is always a call to return home.

Always remember being Chinese

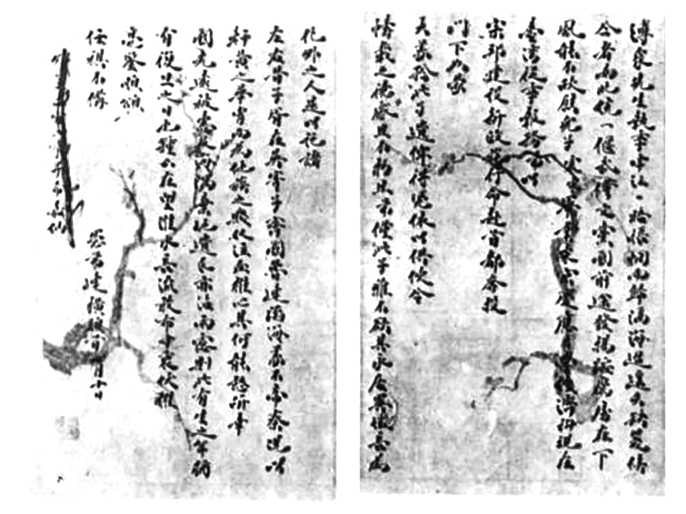

In 1931, Lien Chen-tung brought a handwritten letter from his father, Lien Heng, on a trip to Nanjing to visit Zhang Ji, a senior Kuomintang official. In the letter, the elder Lien wrote with deep emotion, “This is my only son. I do not wish for him to remain in a foreign land and live his life as an outsider. I therefore entrust him to you and your colleagues.”

Lien Heng (1878-1936), a native of Tainan on the island of Taiwan, was a renowned patriotic poet and historian of modern China, best known for his work A General History of Taiwan.

In 1895, following China’s defeat in the First Sino-Japanese War, commonly known in China as the Jiawu War, the Qing court ceded the island of Taiwan and the Penghu Islands to Japan. Lien Heng’s father died in grief and anger as a result.

Faced with the pain of national humiliation, his father’s death, and the loss of home, Lien Heng never forgot that he was Chinese. He swore never to become a subject of a lost nation, nor to take Japanese citizenship. To prevent his son from becoming, in his words, “a base slave of another race,” Lien Heng, still on the island of Taiwan at the time, asked Lien Chen-tung to take his letter to his old friend Zhang Ji.

In the letter, Lien Heng invoked ancient examples to draw parallels to his own act of entrusting his child to others. This noble and righteous sentiment deeply moved Zhang, who arranged for Lien Chen-tung to stay and work in the mainland.

To preserve and pass on Chinese culture, Lien Heng himself chose to remain on the island of Taiwan. In a letter to his son, he wrote, “To liberate Taiwan, we must first build the motherland. I must remain here to preserve Taiwan’s documents and cultural records.” Over the following three years, Lien Heng wrote nearly every week to his son and daughter in the mainland.

In another letter, he wrote, “My son must understand that every stroke and line is tied to the survival of our cultural heritage. Should we lose the rules that govern our writing, Chinese literature will be silenced forever.”

Words cannot capture the depth of longing

“May we, as brothers, come to understand that life’s journey – after enduring hardship and adversity – calls for us to cherish our health all the more, and to embrace the blessings life has to offer.”

In 1989, when a fellow villager from Kinmen planned to visit the Chinese mainland, Chen Zhenchao, a local resident, entrusted him with a handwritten letter and the search for his younger brother Chen Yixiang in his hometown of Fuzhou, East China’s Fujian Province.

After re-establishing contact with his family, Chen flew from Taiwan to Fuzhou via Hong Kong. At the airport, reunited with his relatives after decades, the torrent of emotions in his heart was distilled into a single sentence: “It’s enough that you are alive.”

After returning to his hometown and reuniting with his loved ones, he made three heartfelt wishes in his letter: to repair the family’s ancestral tomb, to renovate the ancestral home, and to financially support several younger brothers.

Chen was born in 1923 in Fuzhou and in 1947, he moved to Taiwan and worked at the so-called “department of finance” on the island. He passed away in Kinmen in 2014.

When Chen left Fuzhou for Taiwan, he was in his prime and both parents were still alive. However, when he first returned to his hometown decades later at the age of 66, his parents had already passed away. On their deathbeds, they remained deeply concerned about their eldest son who had left for Taiwan island and never sent word – a lifelong sorrow that weighed heavily on Chen’s heart.

‘Never forget to come home’

“I have waited for decades, praying to the gods day and night, asking only to see you once more before I die. But that day will never come. I know I cannot escape this fate. Perhaps by the time you receive this letter, I will already be gone.”

This letter was sent to Huang Jianzhong, the only son of Huang Ajiu and Huang Baolan. He was the youngest among those taken from Tongbo village to Taiwan. He was just 17 years old.

In May 1950, on the eve of the liberation of Dongshan Island in East China’s Fujian Province, retreating Kuomintang remnants frantically conscripted young men to replenish their ranks before fleeing to the island of Taiwan. Overnight, 147 able-bodied men were taken from Tongbo village.

After these men were taken, their elderly parents, newlywed wives, and orphaned children left behind on the mainland struggled both materially and emotionally.

In 1963, Tongbo village received its first letter from the island of Taiwan, which had taken a circuitous route through Singapore. From then on, the families of those who had been taken began writing letters in hopes of reaching their long-lost relatives.

By the 30th year of separation from her son, Huang Baolan’s health had deteriorated to the point of no return. Before she died, she asked someone to write a final letter on her behalf.

“Before I leave this world, I have one last thing to tell you: When peace finally returns, never forget to come home,” the mother told her son.

‘In this sacred war, I have fulfilled my duty’

“Now that the war has been won and our homeland has been recovered, you should feel proud of and honored by your son and daughter who fought for nine years… In this sacred war, I have fulfilled my duty.”

In 1945, upon hearing the joyous news of Japan’s surrender, victory in the Chinese People’s War of Resistance against Japanese Aggression, and the restoration of the island of Taiwan, 30-year-old Lin Zhengheng was overwhelmed with emotion. Using his disabled hands, he wrote a long letter to his mother recounting his eight years of wartime experience.

“The restoration of Taiwan has realized the lifelong aspiration of my father. If he were still aware, he would surely laugh joyfully in the afterlife… If the country can achieve victory and grow stronger, if our compatriots in our homeland can gain light and freedom, then it is worth it, even if I am crushed to pieces.

Lin Zhengheng (1915-50), a native of Taichung in Taiwan, was the son of renowned patriotic general Lin Zumi and the eighth-generation heir of the Wufeng Lin family. After the Lugou Bridge Incident broke out in 1937, Lin resolutely abandoned his studies and joined the army, applying to the army officer school in Nanjing. After graduation, he took part in the Battle of Kunlun Pass in South China’s Guangxi Zhuang Autonomous Region, where he dealt a heavy blow to the invading Japanese forces.

In early 1944, when the Kuomintang government organized the Chinese Expeditionary Force to fight against Japan in Myanmar, Lin volunteered without hesitation.

During combat, Lin sustained 16 injuries and lost consciousness. He miraculously survived after undergoing two major surgeries.

In 1946, Lin secretly joined the Communist Party of China and returned to the island of Taiwan to carry out revolutionary activities. In August 1949, Lin was arrested by Kuomintang authorities at his home in Taipei. In January the following year, he was executed, which he faced with bravery.

‘Water has its source, and trees have their roots’

“Towering trees must have roots; mountain streams must have their source.” This line captures the essence of a letter exchange between Huang Tianzhu and Huang Zongji – a story of a Taiwan compatriot’s journey across the Straits in search of his ancestral roots.

Born in 1930, Huang Zongji was born in Penghu county, the island of Taiwan. In 1985, during a return trip to Penghu to honor his ancestors, a casual conversation with relatives about the unknown origins of their forebears left him restless and sleepless. “Water has its source, and trees have their roots” – driven by this conviction, Huang became deeply involved in organizing the Kaohsiung Huang Clan Association.

In May 1989, Huang joined the association on a long-awaited pilgrimage to his ancestral homeland in Quanzhou, East China’s Fujian Province. There, he met fellow clansman Huang Tianzhu, a specially appointed researcher at the Quanzhou Museum, and entrusted him with the task of helping continue the search for his family roots.

After four years of correspondence and help from Huang Tianzhu and Tong’an clansmen, in 1992 Huang Zongji traced his Penghu family’s roots to Neicuo village in Jinjiang, Fujian.

In recent years, more and more Taiwan compatriots have journeyed to the mainland to trace their roots and pay tribute to their forebears, a vivid testament to the shared bloodline and cultural bonds that connect people on both sides of the Taiwan Straits.